RA Perspectives: Caitlin Lynch

- mvbelhaj

- Dec 18, 2024

- 3 min read

Updated: Mar 20

Examining the Need for Housing as a Climate Refuge

Written by Caitlin Lynch, HSHE Research Assistant

The climate crisis poses a significant threat to public health and housing security. As extreme weather events such as floods, hurricanes, and wildfires become more common, and unpredictable temperatures make cooling homes increasingly cost-prohibitive, investment in climate-resilient housing is essential to the promotion of public health. Climate change is uniquely positioned to exacerbate major housing challenges, including shortages of housing stock and weatherized homes, environmental injustice, and homelessness.

More than half of reported displacements in 2022 were attributed to climate-related disasters, and an estimated 1.2 billion people could be displaced due to weather-related natural disasters by 2050. The United States already faces an estimated shortage of four to seven million homes. As extreme weather damages existing housing stock and migration events raise the demand for housing, there will be increased pressure to provide climate-resilient housing at scale.

While the need to limit global temperature rise to 1.5ºC is urgent, monitoring and controlling temperatures inside homes must also be recognized as a public health priority. Almost half of individuals who died due to extreme heat in the past twenty years died at home, indicating that homes are not providing adequate protection. Research has demonstrated the potentially fatal consequences of extreme heat, and found that significant housing weatherization is needed in Detroit, Cleveland, Buffalo, and Milwaukee. Federal assistance from the Department of Energy’s Weatherization Assistance Program is a step towards safety within the home, while simultaneously creating job opportunities and lowering energy costs. Home weatherization also benefits the climate, reducing energy usage through insulation and minimizing air leakage. Given that residential energy use accounts for ~20% of greenhouse gas emissions in the US, housing is a high-potential area for climate progress.

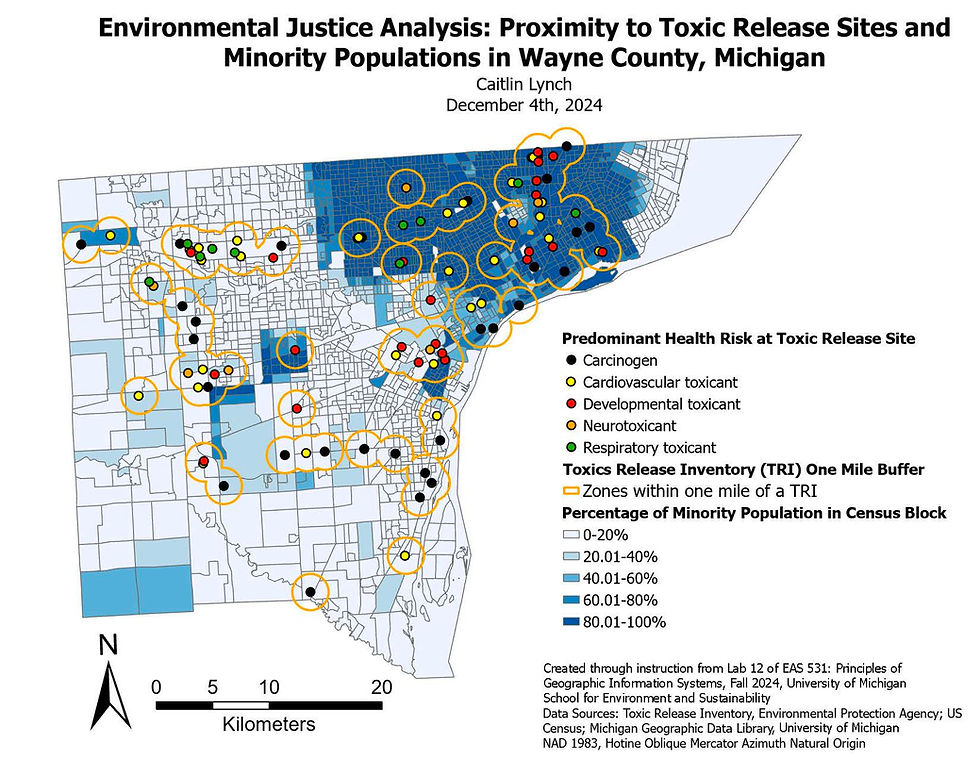

Instances of environmental racism in health and housing are well-documented, particularly relating to increased exposure to lead among African American children, the effects of urban heat islands, and the presence of toxic release sites in communities with high percentages of minority residents (Figure 1). Climate change also exacerbates the persistent effects of racial discrimination in housing. Research shows that communities that experienced redlining are at a higher risk of flooding than non-redlined areas. These same areas are now vulnerable to “bluelining,” wherein insurance companies charge higher rates or cease coverage for properties more likely to experience environmental damage. Bluelining is expected to disproportionately affect low-income communities and communities of color, resulting in climate-related financial inequality. Regulations are necessary to ensure that climate change is not an avenue for financial exploitation of minoritized populations.

Increased protection from climate-related risks should be provided to homeless individuals and families. Homeless individuals are more vulnerable to extreme heat and cold, lacking consistent access to weather protection from housing. In California, homeless people comprised 13% of hospitalizations involving heat illness from 2017-2021, despite making up under half a percent of the population. Climate risks only further the critical need to make housing accessible to homeless individuals.

In addition to strengthening the durability of individual homes, urban planners should assume a community-based approach, which can include leveraging municipal infrastructure. Public libraries, for example, have become common heating and cooling sites. The Detroit Public Library has served as a cooling center for decades, and a public library in Missouri offers crafting events and family-friendly movies during weather-related events. In Los Angeles, a resilience hub offers cooling as well as community events in an environment that seeks to be comfortable and consider “local nuances” that contribute to higher-quality service. Whenever possible, climate relief and housing services should seek to promote dignity, safety, and comfort.

Specialized care should be taken to support rural communities, which may face challenges accessing disaster relief due to geographic isolation. In particular, experts find that rural areas need frequent monitoring of their water collection systems, as flooding has been found to pose a particularly high risk to decentralized rural water systems and private wells. Research has shown the compounding challenges faced in rural homes when flooding leads to mold growth, and subsequently, respiratory issues.

As the effects of climate change worsen, community and municipal leaders should work in conjunction with public health and environmental science experts to promote harm reduction and ensure that the home is a place of protection and comfort.

Commentaires